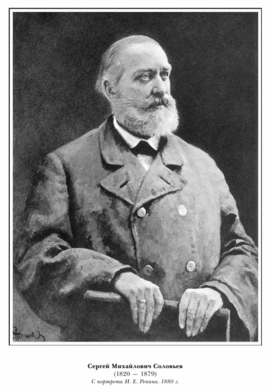

Soloviev Sergey (1820–1879) – historian, specialist in Russian history and culture.

He graduated from the Historical and Philological Department of the Philosophical Faculty of the Moscow University in 1842. In 1842-1844, he travelled abroad as a private teacher at the family of Count S. G. Stroganov; thanks to it S. had a chance to visit lectures at the Universities of Paris, Berlin, and Heidelberg.

In 1845, he defended his Master thesis ‘On the Relations of Novgorod and Moscow Great Princes’; in 1847, he defended his Doctor thesis ‘The History of Interrelations of Russian Princes of the House of Riurik’.

He was free lance Professor at the Chair of Russian History at the Historical and Philological Department of the Philosophical Faculty of the Moscow University (1847-1850); Full Professor (1850-1870); Dean (1855-1869). He was a member of the Committee on the Preparations of Festivities by the 100th Anniversary of the Moscow University.

As rector of the Moscow University (1871-1877), he promoted the foundation of the High Female Courses, and the Surgery, Legal, and Medical Societies. In 1876, in a group of 35 Professors, he signed an Open Letter against the position of Prof. N. A. Liubimov on the reform of Russian universities. The Ministry of Education supported Liubimov, so, S. had to leave the position of Rector.

Honoured Professor of the Moscow University (1859); Honoured Member of the Moscow University (1878); Chairman of the Society of the History and Russian Antiquities (1879); Correspondent Member (1864) and Academician of the Ac. of Sc. (1872) at the Dep. of Russian Language and Literature (Russian History); Director of the Armoury (1877-1879).

He considered that religion was the top point of the social life, and the religious culture of a certain corresponding period, was described in each chapter of his fundamental work ‘The History of Russian since the Most Ancient Times’. He was sure that the role of religion was growing at the crisis or crucial moments, and it influenced more at other spheres of culture. Particularly, he saw a special role of Christianity not only at the shaping the Russian state, but also at the legal structure, family life, and morality. Thus, on his opinion, the new religion provided the evolution of the Old Russian society in various directions during the fragmentation of the state (Second Half of the Eleventh – Mid-Thirteenth Cent.), when Orthodox clergy actively participated in political events, establishing peace between princes and pacifying the people rebellions. He put a special attention to the Dissent of the seventeenth century. Speaking about the Old Believers, he set aside his general opinion about the transformative will of common people always in the direction of strengthening the state. He admitted that in practice not everybody understood the necessity of the Church reform. He believed that the authorities could escape the Dissent through education and enlightening people. He argued that the anti-Church movement could not appear with proper conscience of common priests who would be able to explain their congregations that the ‘novelties’ were a return to the pure old canons.